LA Asian Pacific Film Festival 2009: an interview with Sounds of a New Hope director Eric Tandoc

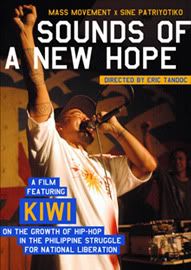

Eric Tandoc's short film Sounds of a New Hope draws connections between music and politics, the Philippines and Filipino America. APA talks to the director about striking the right balance to strike the most provocative chord.

Documentary filmmakers are the underdogs of cinema. They live in poverty, struggling between intermittent stretches of grant funding. They shoot their footage in completely wild and unforeseeable conditions, and are often prone to the most cruel and unhappy kinds of accidents. Yet, for all the hard-fought footage, the countless hours of tedious editing, and of course, the lack of funding, the documentarian must always ask himself, "What is the end result of this work?"

For Eric Tandoc, all of this work and labor in documentary has an eventual point -- the creation of community and of relations between people. It is the hope that documentary as an art will have the ability to share and empower viewers, and give a voice to the unheard. With his new film Sounds of the New Hope, Tandoc wants to put the microphone to the mouths of storytellers who have not been able to tell their story before. In the film, he follows the Filipino American MC, Kiwi, as the young rapper grows from his brash youth as a gangbanger on the streets of Koreatown to radical political activism promoted throughout the slum-dwellings of the Philippines. But what makes this film so fresh, exciting, and relevant is that Kiwi wants to translate the rough material of real politics and class struggle through the word and rhyme of hip-hop. Like an improvement on Aristotle's notion that what makes a human political is his ability for speech, Kiwi transforms the flow of his rap into a tool that constructs a unity and kinship. Kiwi uses rap as a bridge for the impoverished Filipino to communicate. Rapping, it seems, is a much more immediate mechanism for saying what's on your mind. And much like Kiwi, Tandoc wants to use the tools of documentary to create these same bridges and to tell stories that are much more than stories. For Tandoc, the end result of a documentary should be action: to turn back, reflect, and serve a community.

Asia Pacific Arts: Could you tell us a little about yourself and the short film that you have playing at this year's festival?

Eric Tandoc: My name is Eric Tandoc, and I'm a 29 year-old second-generation Filipino American who was born in San Diego and grew up in Long Beach. Aside from filmmaking, I'm a community organizer and member of a youth and student organization called AnakBayan and a progressive arts organization called Habi-Arts. Both of these organizations are part of a national alliance called Bayan USA, which consists of 14 organizations across the country that support the struggle for national liberation and genuine democracy in the Philippines, as well as the struggles of Filipinos living here in the United States. In addition to that, I'm a DJ in a hip-hop crew called Mass Movement and an emcee in a live hip-hop band called The Committee.

My latest documentary, Sounds of a New Hope, chronicles the life and music of Filipino American emcee and community organizer, Kiwi, as well as the growth of hip-hop as an organizing tool in the movement for genuine freedom and democracy in the Philippines. It was created as my thesis film for the UC Santa Cruz Social Documentation M.A. program.

The film documents Kiwi's life growing up around youth gangs in the Koreatown area of Los Angeles and how he later became involved in hip-hop and community organizing in the Filipino community. Then the film fast forwards to his current organizing work through hip-hop workshops with youth in San Francisco at the Filipino Community Center. The second half of the film follows him on his political exposure trip to the Philippines in 2007, where he is hosted by AnakBayan and integrates in urban shanty communities. There, he meets youth gangsters who rap and connects with their experiences through the common language of hip-hop.

APA: Do you have any good anecdotes of working on this documentary while following Kiwi around the Philippines?

ET: Although the film focuses on Kiwi's experiences rapping with urban youth in the shanty communities of Caloocan, we were also able to connect with some of hip-hop's elite in the Philippines -- Francis M and Gloc 9. Francis M is considered the "King of Philippine Rap," since he was the first Filipino to ever release a hip-hop album back in 1990. What's great is that his songs are also very nationalistic, rapping about positivity and believing in ourselves as Filipinos. When we first met him, he told Kiwi how he'd been following his music with Native Guns since 2005 and frequently played their songs on the radio show that he hosted. Kiwi got to build a friendship with him and when Francis suddenly passed away from leukemia earlier this year, he took it really hard. We are all saddened by the loss of a legendary figure in Philippine hip-hop.

Gloc 9 is one of his talented protégés and had several songs on the radio while we were there. He's known for super-fast rhyming and talking about the struggles of growing up poor. But the ironic thing is, even though he's well known and has songs on the radio, he recently enrolled into nursing school and has aspirations of going abroad to work. I remember him saying how if he were able to financially support himself and his family through nursing, then he could be free to fully pursue rapping. I think it's a reflection of the Philippines' semi-colonial and semi-feudal economy that even a big-name rapper like Gloc 9 isn't able to make a living off his art and is forced to follow the thousands of Filipinos who leave the country every day just to survive and support their families.

APA: This is a piece about the mixture of music and politics, of hip-hop and massive political movements in the Philippines in a very literal way. Tell us more about the relation of music and politics?

ET: Kiwi and I both identify as cultural workers, meaning we create our art for the purpose of educating our communities in order to raise people's political consciousness and hopefully inspire them to take action and work towards creating systemic change.

Music, and hip-hop in particular, is a powerful and direct way of conveying messages through personal expression. Often times, it's more effective than speeches or forums as a way of sparking interest in political or social issues. Music, like other forms of cultural work, connects with people's emotions in such a way that one can really feel the humanity and beauty found in the struggle for a better world.

Music can reflect the realities of people and society, but it also shapes reality. A song can be highly influential and infectious, as it can inspire you to memorize lyrics and even cause you to behave in ways that manifest the values in those lyrics.

APA: You studied documentary here at UCLA. How has that influenced your growth as a young filmmaker and documentarian?

ET: As an undergrad at UCLA, I was introduced to documentary filmmaking through the History of Documentary Film course taught by Marina Goldovskaya. Through her Documentary Production Workshop, I made my first visual life history documentary about my grandmother, called Nanay.

Subsequently, I took the year-long UCLA EthnoCommunications course taught by Robert Nakamura and John Esaki and became grounded in the principle of creating documentaries to give a voice to underrepresented communities. Through this course, I created 810LOGY, a short documentary about the history and growth of my multi-ethnic skateboard crew from Long Beach and our struggles with gangs, discrimination, and police harassment.

Through studying documentary at UCLA, in addition to having wonderful professors as mentors, I was exposed to amazing films such as Beats, Rhymes, & Resistance: Pilipinos and Hip Hop In Los Angeles by Dawn Mabalon, Lakandiwa de Leon, and Jonathan Ramos; Koyaanisqatsi by Godfrey Reggio and Ron Fricke; Style Wars by Tony Silver and Henry Chalfant; and A Rustling of Leaves: Inside the Philippine Revolution by Nettie Wild. All of these had profound influences on the style and approach of the documentary films that I make. Before then, I had only associated documentaries with boring history channel "Voice of God"-style films. But these films showed me the diverse creative possibilities of the documentary medium.

APA: What's next in store for you in terms of your documentary work in the Philippines and here in America, and also with regard to your musical interests?

ET: We plan on taking Sounds of a New Hope on a concert tour around the US later this year and intend to hold the LA community premiere at UCLA. As for future projects, this summer I plan to work with AnakBayan and Habi-Arts to conduct documentary workshops with youth and educate them on how to produce visual life history documentaries about their parents and their experiences as immigrants from the Philippines. I'm also working on an ongoing video documentary about my cousin Mark Canto, who is an artist and first-generation immigrant, called Mass Movement: Roots.

In the future, I hope to continue making films raising awareness about the people's struggle in the Philippines as well as the culture of Filipino Americans here in the United States. I'm interested in documenting the contributions of Filipino Americans to youth culture, music, and American society as a whole. One day, I also hope to be able to make a feature narrative about critical events in Philippine history.

Regarding music, I'll always continue to DJ, make mix tapes, make beats, and develop my skills as an emcee. Currently, an album is in the works and will hopefully be released by next year. All the while, I'm continuing to perform and create songs with my band, The Committee.

Date Posted: 5/22/2009

reposted from: http://www.asiaarts.ucla.edu/090522/article.asp?parentID=108464